HOW LEONARD

COHEN FOUND

HYDRA

Text by Ira B. Nadel

Photos by Charles Gurd

Drawings by Leonard Cohen

In March 1960, when he had completed his manuscripts, Cohen was free to consider his position in London, and he found it wanting. After having a wisdom tooth pulled one day, he wandered about the East End of London on yet another rainy afternoon and noticed a Bank of Greece sing on Bank Street. He entered and saw a teller with a deep tan wearing sunglasses, in protest against the dreary landscape. He asked the clerk what the weather was like in Greece. “Springtime” was the reply. Cohen made up his mind on the spot to depart, and within a day or so he was in Athens. “I said to myself that I should go somewhere completely different in order to see how they live,“ he later explained.

It was actually the island of Hydra that attracted Cohen. English was spoken and an artists’ colony was flourishing. He had first heard of Hydra from Jacob Rothschild, whose mother had married Ghikas (Niko Hadjikyriakos), one of modern Greece’s most important painters. They lived in his family’s forty-room seventeenth-century mansion perched on a hill some distance from the port with a striking view of the sea. Jacob Rothschild encouraged Cohen to visit his mother, promising to write to her to say that Cohen was coming. Layton had predicted Cohen’s departure. “I suppose when he’s finished his novel,” he told Desmond Pacey, ”he’ll leave London for the Continent, where he’ll make love to all the beautiful French and Italian women, and then leave for Greece and Israel!”

Cohen arrived in Athens on April 13, 1960, visited the Acropolis, then spent the night in Piraeus. The next morning he began the five-hour steamer journey to Hydra, which took him first to Aegina, Methana, and Poros, and then to Hydra. (since the seventies, the Russian-built Flying Dolphins hydrofoils have replaced the once-elegant steamers, reducing the travelling time to one and a half hours.) The trip was an opportunity to relax, drink, and meet women.

At Hydra, the small semicircular port is flanked by white houses rising steeply in an orderly manner, like the seats of an amphitheatre. A cobble esplanade runs along the waterfront, harmonizing the cluster of homes that surround it and reach up the hillside. Only the bell tower of the cathedral attached to the Monastery of the Virgin’s Assumption disrupts the horizontal tableau. The structure of the town emulates the classical theatre of Epitaurus, with the port the equivalent of the orchestra. Access to and from the port follows the theatrical frame of the parodos (side entrances and exits) with the houses mimicking the stepped seats of the theatron. Towering above the port is the two-thousand-food Mount Ere, and on a high hill just below it, the Monastery of Profitis Elias (the Prophet Elijah).

In the morning the port is the commercial center where boats are unloaded, where fish and vegetables are sold, and donkeys are hired. At midday and into the evening it becomes the social center, the focus turned toward the restaurants and cafes. During religious or public holidays, it is the site of celebration. When Cohen arrived in 1960, only four coffeehouses and one bar ringed the waterfront.

Tradition, rather than a master plan or building code, determined the urban layout and architecture of Hydra. When a child married, a new house was built within the uncovered space of the family lot, treated as a separate unit, and given entry from the public street. The result was odd lot shapes and dead ends (most houses are rectangular or “L” shaped and composed of stone walls, timber or tile roofs, and tile floors.)The doorways are unique in that they face downwards to the port, rather than horizontally to the street. Offsetting the whitewashed walls of the homes are the orange tile roofs and weathered cobblestone steps. It was the anarchy of the homes that prompted Henry Miller to remark on the “wild and naked perfection of Hydra.”

The narrow island was named for water though it actually has little. Rain is rare, the averange yearly precipitation being only an inch and a half. When the first home with a swimming pool was built by a Greek American in the late sixties, the owner had to pay for barges of fresh water to be brought in and pumped up the hilly streets. It is little more than a barren rock, four miles wide and nearly eleven miles long, about four miles off the southeast coast of Argolis.

There are no cars or trucks on Hydra, since the land is too steep and the streets too narrow to permit them. Donkeys, witch bray in an agonizing manner throughout the night, and occasionally horses, are the only transportation on the steps and ramps. The widest streets were originally designed so that two basket-carrying donkeys could pass each other; secondary street provide passage for only one. An important site is Kala Pigadia, the Good Wells or Twin Wells. Situated above the port, this is where water was drawn and people gathered to trade news and stories; the two small wells are shaded by several large trees.

When Cohen first arrive on Hydra there was limited electricity, few telephones, and virtually no plumbing. Kerosene or oil lamps lit the homes; cisterns were used to collect water, and no wires obstructed the views. One of the views disco used a battery-operated record player, since the small electrical plant generated power only from sundown to midnight. Except for the kitchen, which was heated by the stove or Turkish copper braziers, rooms were heated with a three-legged tin filled with charcoal embers. Many of the homes were run-down and in desperate need of repair. In 1960, half of the homes were uninhabited, and virtually no new homes had been built for nearly a century.

Cohen first met George and Charmian at Katsikas’ Bar, which consisted of “six deal tables at the back of Antony and Nick Katsikas’ grocery store at the end of the cobblestoned waterfront by the Poseidon Hotel.” Amid flour sacks, olive jars, and strings of onions, an artist’s club of sorts flourished. Evenings were spent arguing, drinking, and entertaining one another. George, the writer-in-residence, held court, often speaking “in a wild spate of words, punctuated with great shouts of laughter and explosion of obscenity.” Members of the foreign community appeared, withdrew, and reappeared. The port became a “horseshoe-shaped stage” and the Johnston’s circle “the actors of some unbelievable play the intriguing plot of which unrolled in front of the eyes of a totally flabbergasted audience---the locals, who watching it all commented on the side like the chorus of an ancient Greek tragedy.”

Cohen soon joined in, absorbed by the discussions, social relations, and sexual maneuverings of his new crowd. He gave his first formal concert at Katsikas’ grocery and formed an important and lasting friendship with the Johnstons. They gave him a big work table that he used for writing and eating, as well as a bed and pots and pans for his new house.

|

|

On September, 1960, six day after his twenty-six birthday, Cohen bought a house in Hydra for $ 1500, using a bequest from his recently deceased grandmother. This was a “big deal” in the words of one of his friends, a commitment to a place and a word that was mysterious and unusual. Buying the house was a complicated act, needing the assistance of his friend Demetri Gassoumis as translator, adviser, and witness to the deed. Cohen later said that it was the smartest decision he ever made. The three-story, ancient whitewashed building, with its five rooms and several levels, was run-down and had no electricity, plumbing, or running water. Yet it was a private space where he could work, either on the large tiled terrace or in his music room on the third floor. Cohen described his home to his mother:

|

It has a huge terrace with a view of a dramatic mountain and shining white houses. The rooms are large and cool with deep windows set in thick walls. I suppose it’s about 200 years old and many generations of seamen must have lived here. I will do a little work on it every year an d in a few years it will be a mansion… I live on a hill and life has been going on here exactly the same for hundreds of years. All through the day you hear the calls of the street vendors and they are really rather musical … I get up around 7 generally and work till about noon. Early morning is coolest and therefore best for work, but I love the heat anyhow, especially when the Aegean Sea is 10 minutes from my door.

|

In a letter to his sister he recounts the nights:

I wonder through the rooms with a candle like Rebecca’s housekeeper, upstairs, the scary basement; my land (presently a garbage heap) is home for a couple of mules and the tinkle of their bells as they pick for food can break your heart as blends with the music of a taverna two o’clock of a Monday morning. The wind brings you the sound, or three young men, their arms about each other’s shoulders, singing magnificent close harmony, nasal [.] Turkish minors fill the street with their shared pain of abandoned love, as they reel past your door…. There are about sixty countries I’ve got to visit and buy houses in.

Cohen also adopted the island tradition of keeping cats, although at first he tried to chase them away: “But day came back. I am told that it is the custom of the island to keep cats, and who am I to defy custom?” He relegated them to the basement, since they might have given him hives.

|

He knew he had been accepted by the community when he began receiving regular visit from the garbage man and his donkey. “It is like receiving the Legion of Honour.” Cohen’s house gave him a foundation. To a friend he explained that “having this house makes cities seem less frightening. I can always come back and get by. But I don’t want to lose contact with the metropolitan experience.” Buying the house also gave him confidence: “The years are flying past and we all waste so munch time wondering if we dare to do this or that. The things is to leap, to try, to take a chance.”

|

Greece provided Cohen with a base an observation post on changing social and sexual mores. “The primitive circumstance of my life on this island [are] a condition I hopefully established to attract an interior purity,” Cohen wrote, celebrating the discipline instilled by the island. He also liked the natural magic of the island, which could transform a person; in certain season, one came out of the sea luminous because of the plankton that adhered to the body. On Hydra, he was freed from the social rituals, obligations, and expectations of his Montreal Judaism. He could take responsibility for his own Judaic identity.

Cohen regularly observed Shabbat, lighting candles and saying the blessings at the Friday evening meal. He stopped his work for a day, dressed more formally, and often walked to the port for Shabbat meetings at noon with Demetri Leousi, an islander who spoke a special Edwardian English learned at Robert College in Istanbul. Leousi, who had had a love affair with a Jewish woman in New York when he worked there, sustained a deep affection for Jews and congratulated Cohen on being “the first Hebrew to own property on the island. We are honored.”

Hydra was also cheap. Cohen could live for as little as a thousand dollars a year, and he quickly worked out a scheme whereby he would return to Canada to earn perhaps two thousand dollars and then race back to Hydra to live for a year or so. And the weather was wonderfully warm. In Hydra “everything you saw was beautiful: every corner, every lamp, everything you touched, everything you used was in its right place,” Cohen wrote. “You knew everything you used…It was much more animated, much more cosmopolitan. There were Germans, Scandinavians, Australians, Americans, Dutch who you would run into very intimate settings like the back of grocery stores.” There were no interruptions from work or love. Life was engaging and there was order, but also light:

There’s sun all over my table as I write this, and I’m in love with all the white walls of my house, and anxious to leave them and my stone floored kitchen. I swear I can taste the molecules dancing in the mountains, and I may soon have the privilege of recounting these divine confusions before your fireplace is cold.

The Aegean light had a quality that Cohen felt contributed to his work. “There’s something in the light that’s honest and philosophical,” he told a journalist in 1963. “You can’t betray yourself intellectually, it invites your soul to loaf.” Not surprisingly, Greece began to play a significant part in the poetry which would appear in Flowers for Hitler.

But, just as he felt Montreal both nurtured him and hindered him, Cohen began to feel constrained by Hydra. The attachment to Marianne became both consuming and destroying, a familiar pattern in his later relationships. Island life, with its intense interactions, was becoming difficult. Cohen felt he had to leave for the sake of his art and his peace of mind. The New York poet Kenneth Koch, visiting one summer, reduced the complexities of island life to a single sentence: “Hydra—you can’t live anywhere else in the world, including Hydra.”

In Greece, he explained years later , you “just felt good, strong, ready for the task” of writing. This last remark is a key to Cohen’s method of composition, whether in verse or in song. He cannot work unless he is “ready for the task”, in a state of creative concentration and wellbeing.

Fasting often generated this state, and various friends recall his periods of almost week-long fasts while writing. Fasting also suited the holiness of his dedication to his work, supplement by his desire for discipline.

Although Cohen experienced long fallow periods of non-productivity, he retained a rigid daily schedule. Every morning, Cohen worked either on his terrace or in long, low-ceiling basement study of his home. Only the midday heat interrupted his work; he would then read, swim, and then return to his writ-ing. In Greece, he wrote to Robert Weaver, “there is my beautiful house, and sun to tan my maggot-coloured mind.” |

|

A prose poem entitled “Here Was the Harbour” suggests the purity of life on Hydra that appealed so strongly to Cohen. Describing the harbour and the intense blue of the sky, he proclaims, “Of men the sky demands all manner of stories, entertainments, embroideries, just as it does of its stars and constella-tions.” “The sky,” he continues, “wants the whole man lost in his story, abandoned in the mechanics of action, touching his fellows, leaving them, hunting the steps, dancing the old circles.” In the silence of Hydra, Cohen found his muse, although Greece plays a surprisingly small part in his writing as a subject or scene. Occasional poems describe his life there, but it has no direct presence in his fiction and appears only sporadically in his songs.

Reprinted from the book Various Positions by Ira B. Nadel

with professor Nadel’s kind permission.

More information about the book.

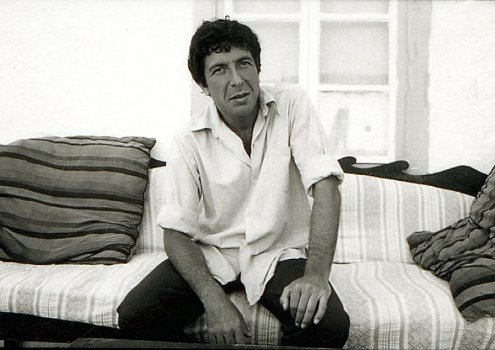

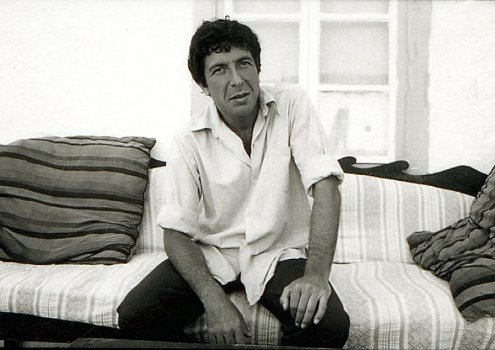

Leonard meditating on his terrace on Hydra:

photos © by Charles Gurd (early 1970’s).

Used with Mr. Gurd’s permission. All rights reserved.

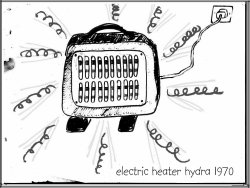

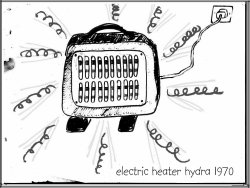

Drawings © by Leonard Cohen. Reprinted here

with permission. All rights reserved.

![[PREV PAGE]](but-prev.gif)

![[NEXT PAGE]](but-next.gif)

![[INDEX PAGE]](but-ndx.gif)

![[SUB INDEX PAGE]](but-subi.gif)

|

![[PREV PAGE]](but-prev.gif)

![[NEXT PAGE]](but-next.gif)

![[INDEX PAGE]](but-ndx.gif)

![[SUB INDEX PAGE]](but-subi.gif)